Happy Thursday and welcome to Patent Drop!

Today, Honda may be placing its hopes on carbon capture to reach bold net-zero goals – despite the tech’s high price tag. Plus: Google wants to take on bias at the source, and IBM wants to help you code.

Let’s take a peek.

Honda Tracks Factory Emissions

Honda wants to make its factories a little bit greener. It may be eyeing carbon removal to do so.

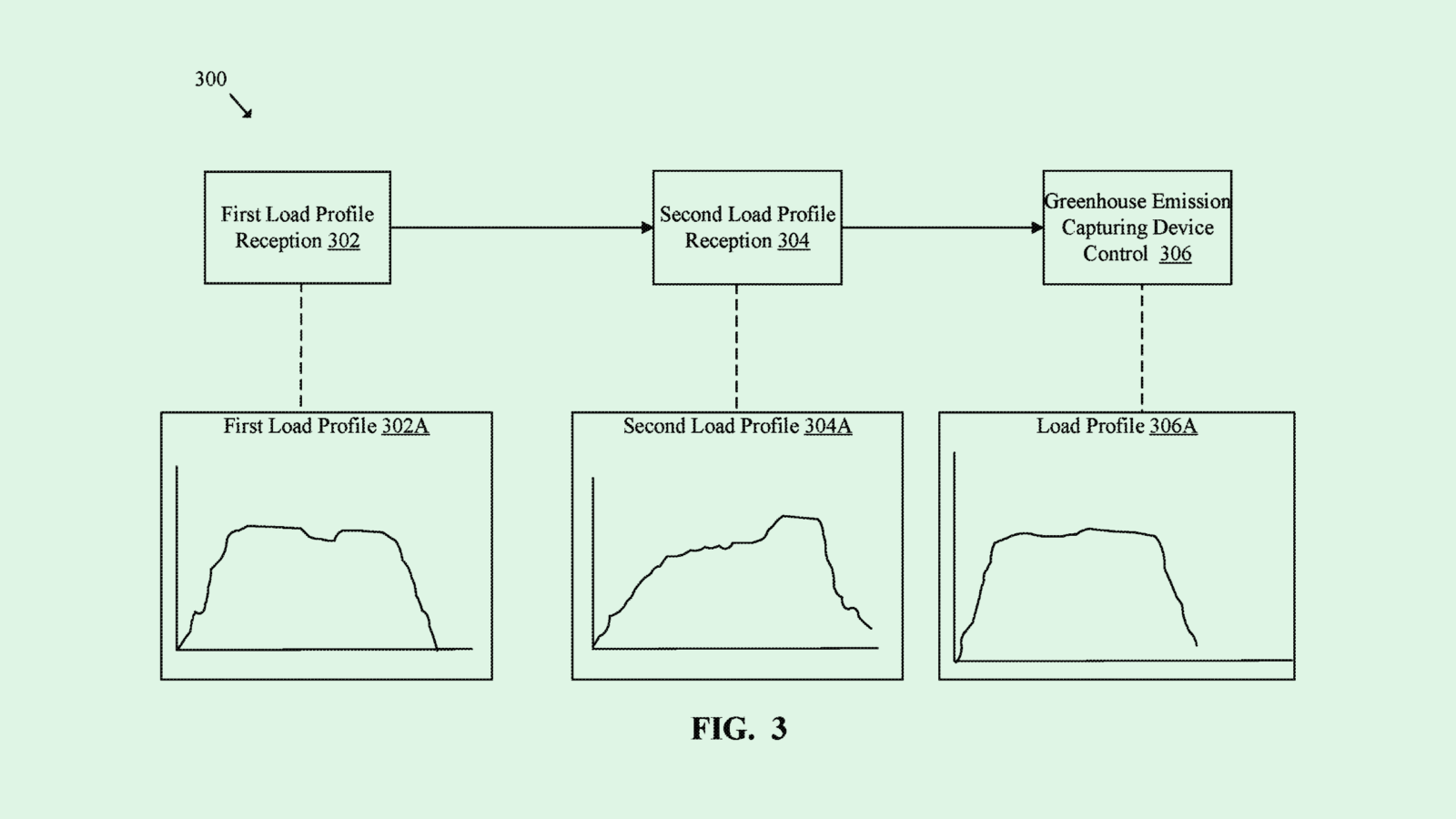

The automaker is seeking to patent a system for creating a “load profile” of factories to remove greenhouse emissions. This aims to estimate and track the emissions of factories and corresponding power plants and remove a certain amount of carbon accordingly.

Honda’s tech aims to “allow the factory to work in tandem with the power plant to reduce overall greenhouse emissions” using direct air capture, the company noted in the filing.

Honda’s system relies on creating “load profiles” for manufacturing facilities and power plants, which track a factory’s energy use and the power generated by the plant to fuel it. This system may also estimate the power consumption of the factory and the power demand of the power plant before the energy has been used.

In response, this system directs a “greenhouse emission capturing device” to remove a certain amount of carbon from the surrounding region. The tracking and estimating of emissions in advance may “increase efficiency of removal of the greenhouse emissions at the time of operation,” Honda noted.

“The greenhouse emission capturing device may work to absorb the greenhouse emissions both from the factory and the power plant to achieve a net zero greenhouse emission, over a certain period of time, such as, a 24-hours period,” the company said.

Honda is one of several automakers with ambitious climate goals. The company aims to be carbon-neutral throughout all corporate activities and products by 2050. The firm also aspires to sell 2 million EVs annually by 2030, and solely zero-emissions vehicles by 2040.

Honda has made some headway through a variety of initiatives, including plans to unveil a new EV line in 2026, investing billions in EV factories in Canada, researching and patenting carbon credit systems for drivers, and even planting 85,000 trees near its factories in Ohio. Carbon capture technology may also be part of its plans to whittle down its emissions to net zero.

In theory, Honda’s patent makes sense: Track and estimate carbon to remove emissions that it has caused over a certain period of time. The concept could help greatly limit Scope one and Scope two emissions, or the ones that the company is directly responsible for, by taking into account the carbon coming from the manufacturing as well as from the plant that’s powering them.

And Honda’s not the only company that may see carbon capture and removal as the answer to undoing emissions they simply can’t cut down. Microsoft, Shopify, Stripe, and other tech firms have also made major bets on the technology.

In practice, however, carbon capture and removal technology simply isn’t there yet, said Daniel Stein, founder of climate giving consultancy Giving Green. “There isn’t really a cost-effective or written removal device that they can reasonably ramp up and down now,” Stein said.

As it stands, carbon capture is far too expensive to do at scale. Removing carbon from the air costs around $600 to $1,000 per ton of CO2, and needs to drop below $200, according to the World Economic Forum. Honda betting on the availability of a highly efficient carbon removal device for the tech in this patent to work, Stein said, is “a little bit aspirational.”

“This really relies on a much more efficient carbon removal system than is currently in operation,” said Stein. “I don’t see how you could actually use this now to get to net zero for a factory, even if the factory was using very minimal electricity.”

Google Strikes a Balance

Google wants to turn bias away at the door.

The company is seeking to patent a system for “rejecting biased data using a machine learning model.” This tech essentially aims to keep bad datasets from entering a model from the jump, thereby preventing a model from developing biases in the first place.

As AI enables the capability to rapidly collect and analyze data, “data processing techniques must equally overcome issues with bias,” Google said in the filing. “Otherwise, data processing, especially for bulk data, may amplify bias issues and produce results also unparalleled to biases produced by human activity.”

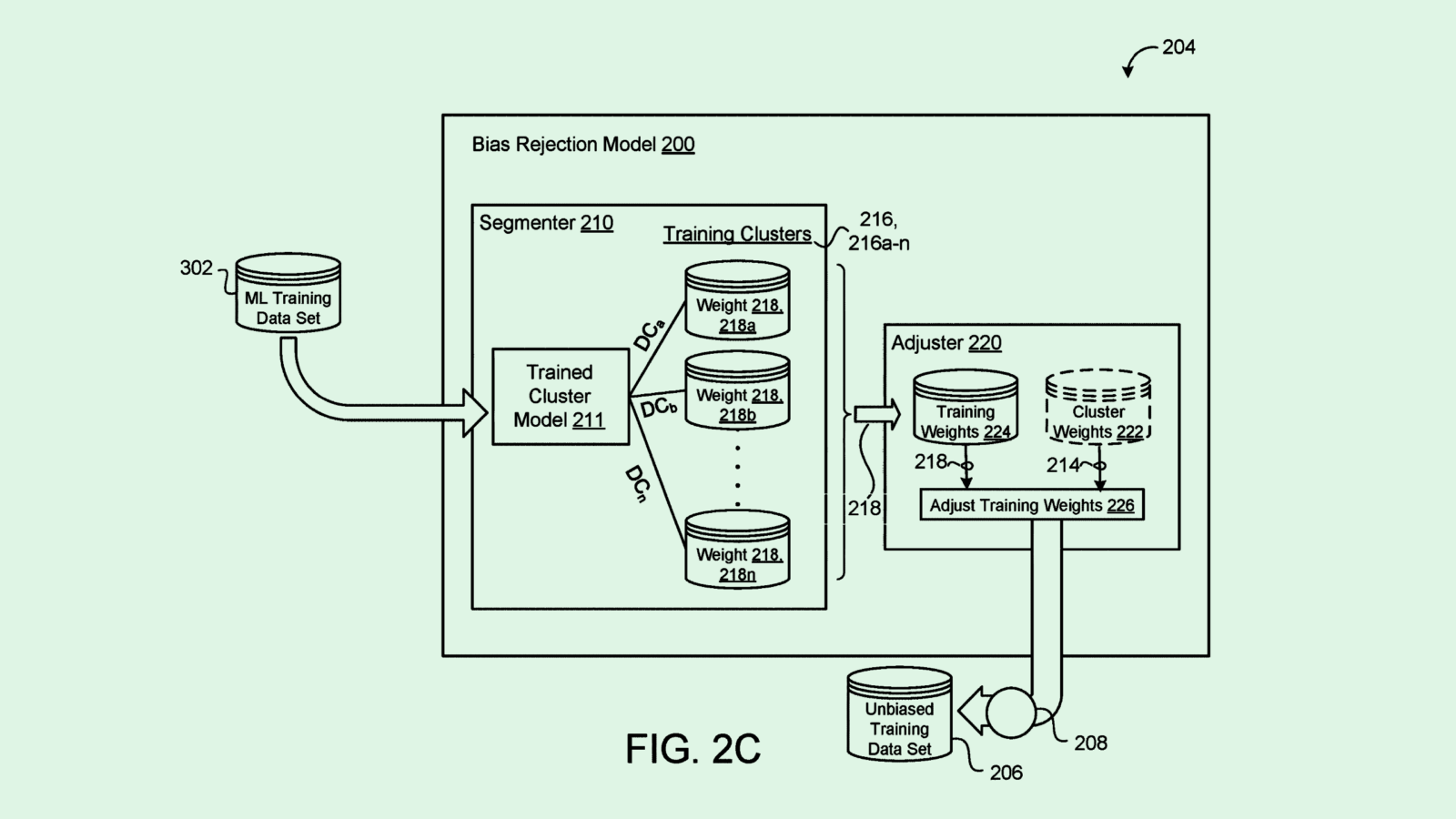

First, Google’s system receives a training dataset that is unbiased and representative of a broader population, which is used to train a “clustering model” that groups similar data points together. This trains the clustering model to put data into categories and properly adjust the weights of data points within the data sets. For reference, the weight of each data point in a data set determines how much influence it has on the machine learning model’s outputs.

Finally, Google’s clustering model is fed other training datasets, which adjust the weights of data points that may be over- or under-represented. While this sounds a bit technical, the outcome of Google’s tech is a way to take bias out of a set of AI training data.

For example, if you have an image data set to train a facial recognition model where more men are represented than women, it may adjust the weights of each category to properly reflect both, making the model less biased and more accurate.

Google’s patent adds to several companies aiming to tackle the ever-present issue of bias in training AI models. AI-inclined tech firms including Adobe, Sony, Microsoft, IBM, and Intel have all sought to patent their own methods of detecting and debiasing for things like image-editing, facial recognition, lending, and more.

An AI model is only as good as the data that it’s trained on. A model taking in a dataset that’s not representative of the task it’s trying to solve will impact its output, with biases growing worse over time. Google’s patent attempts to cut off bias at the source by reconfiguring training data sets, said Brian Green, director of technology ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

However, this patent calls into question just how effective debiasing tools may be on large, general-purpose models, Green noted. Massive generative language models and image generators have to take in a ton of data to handle all manner of queries. However, one model can only go so far, he said. “Every model is going to be limited by its dataset, and every dataset is going to be limited by its sampling,” said Green.

Creating unbiased datasets can also create overcorrections that lead to inaccuracies, Green noted. One example of this is when Google’s generative AI tools came under fire in February after its Gemini image generator created historically inaccurate images of racially diverse founding fathers and Nazi-era German soldiers.

The company noted at the time that its models can create images of a wide range of people, which is “generally a good thing because people around the world use it. But it’s missing the mark here.”

As Google works to get AI in front of more consumers with things like its Pixel smartphone, YouTube AI integrations, and its Gemini chatbot, figuring out bias in widely available AI models is imperative. But the solution likely won’t be simple, said Green. “Ultimately, it’s a really complex problem, and it’s going to require a really complex solution.”

IBM’s Coding Companion

IBM may be working on a Grammarly for software developers.

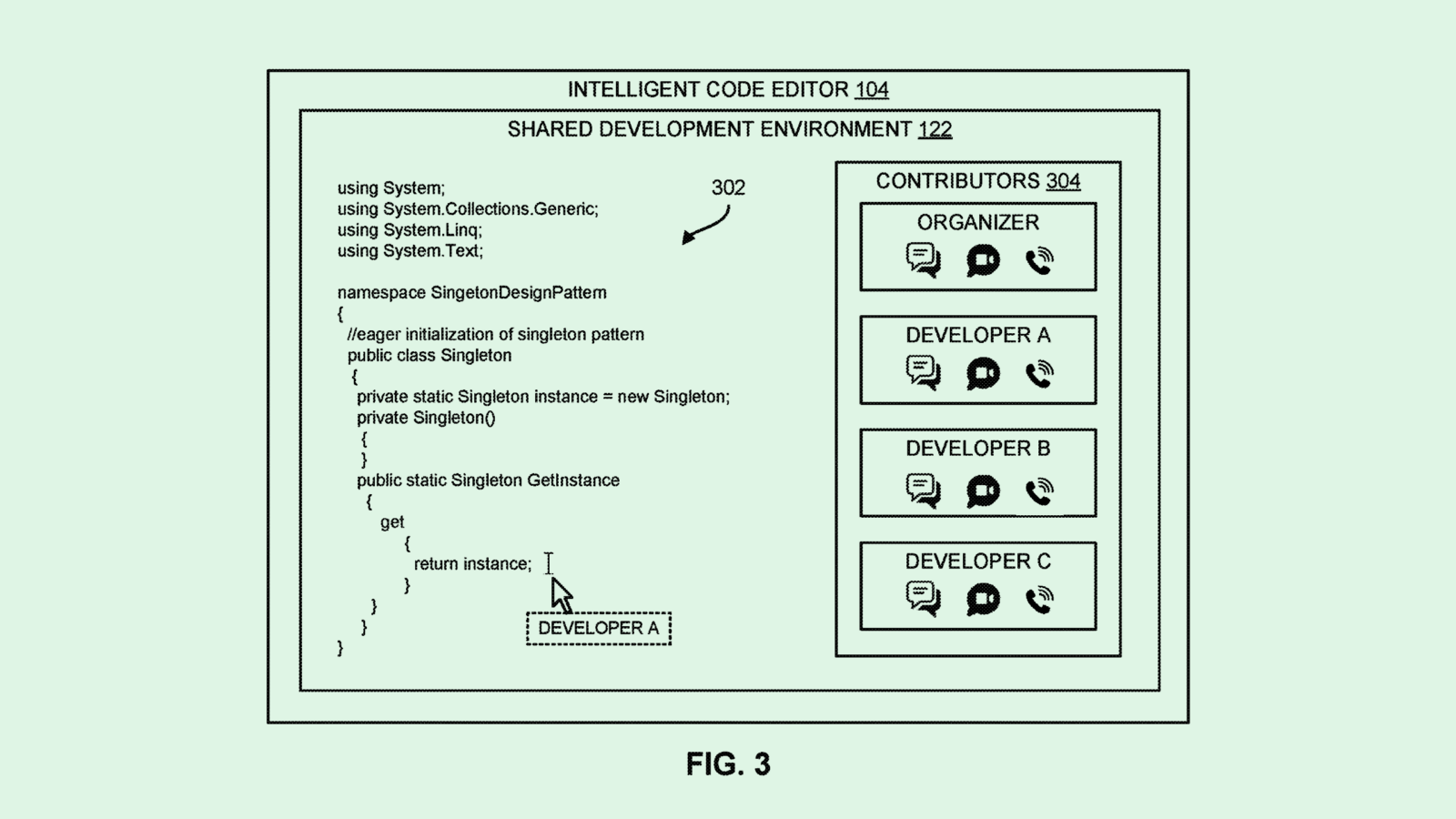

The company filed a patent application for an “intelligent code editor.” IBM’s system would essentially work side-by-side with developers to offer personalized suggestions and recommendations for coding and software design.

“The suggestion features of prior source-code editors have not addressed challenges faced by many of today’s software developers,” said IBM. “The suggestion features of prior source-code editors have not addressed challenges faced by many of today’s software developers.”

Using AI algorithms, IBM’s system would analyze source code samples from a specific developer, aiming to get a feel for their typical coding style and commonly used techniques to make accurate suggestions. Then, as the developer designs code, the system would monitor their work and inputs and offer suggestions on how to improve or build out their designs.

These may pop up as selectable options in the platform that allow developers to accept or reject selections as they see fit. IBM also noted that this tool could show up as a web application or part of a larger development ecosystem that includes things like build automation tools, code interpreters, and debuggers.

Additionally, IBM’s patent outlines a shared development environment in which a group of developers can request assistance from the code editor on specific modifications or suggestions.

The dawn of generative AI has brought coding companions like IBM’s to the fore. One of the most popular options among developers is Microsoft-owned GitHub Copilot, which claims to speed up developer coding by 55%. Google also offers Gemini Code Assist, which relies on the company’s Gemini large language model.

Google also previously filed a number of patent applications for AI software development tools, including a real-time suggestion engine and chatbots for UX design and app development. Meanwhile, companies like Stripe, Oracle, and JPMorgan Chase have sought to patent their own AI-based no-code development tools.

The problem, however, is that AI is often prone to mistakes — massive foundational language models often have a hallucination rate of around 3% to 5%. Research of 150 million lines of code from software company GitClear found a significant uptick in code churn, or code that is changed less than two weeks after being written, in AI-generated code. A study from Stanford came to a similar conclusion, finding more bugs and less security in code created by AI models.

Plus, while these tools AI have the power to supercharge productivity and development, many workers fear that AI may upend their job security. A December workforce report from CNBC and Survey Monkey found that, of more than 7,700 people surveyed, 42% reported feeling concerned about AI’s impact on their jobs.

IBM’s patent highlights that, as it stands, AI can be used as a helpful tool to offer up new ideas or increase productivity. But in many areas, the tech has a long way to go before it can work consistently up to par with human counterparts.

Extra Drops

- Adobe wants to keep your emails on topic. The company is seeking to patent a system for “generating subject lines from keywords” using machine learning.

- Meta wants to keep some DMs kid-friendly. The company filed a patent application for “parental messaging alerts.”

- Snap wants to enhance your poker game. The social media firm filed a patent application for “augmented reality physical card games.”

What Else is New?

- Neuralink ran into trouble with its first in-human brain implant. In the weeks following the procedure, a number of threads from the device retracted from the patients brain.

- Alibaba launched the latest version of its large language model. The company’s AI has seen more than 90,000 deployments.

- Shopify’s shares dropped sharply after earnings guidance suggested that its growth would slow to a “high-teens percentage rate.”

Patent Drop is written by Nat Rubio-Licht. You can find them on Twitter @natrubio__.

Patent Drop is a publication of The Daily Upside. For any questions or comments, feel free to contact us at patentdrop@thedailyupside.com.