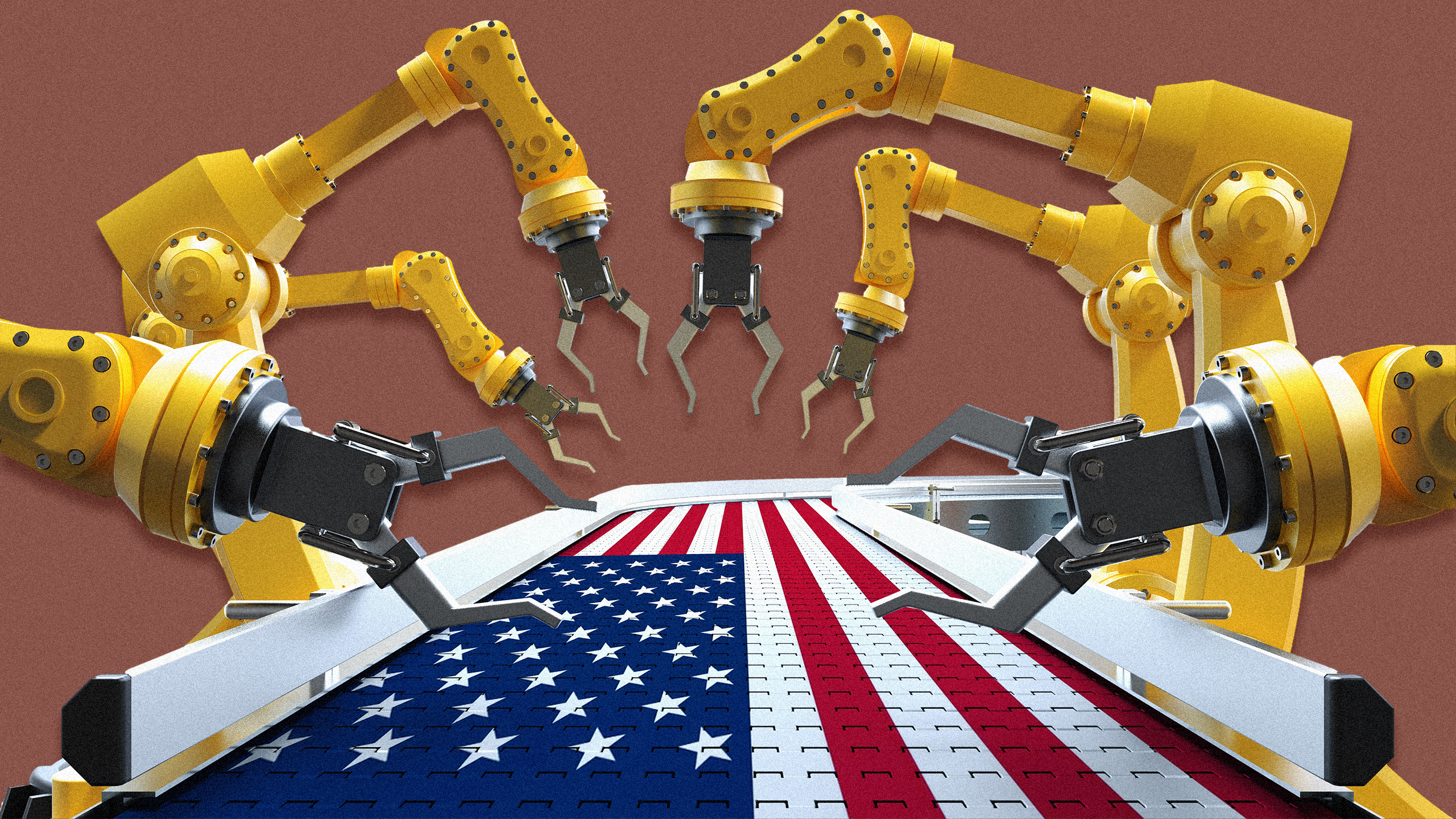

Manufacturing Discontent: Can Tariffs Spur Domestic Reindustrialization?

As a share of US GDP, the manufacturing sector has decreased from a nearly 25% peak in the 1950s to about 11% today.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Since “Liberation Day” earlier this month, tariffs have been imposed, they’ve been rescinded, some have been added back, and some may come back at the end of a 90-day reprieve — barring some artful dealmaking, of course.

Whether more tariffs come back, and what happens next in the global trade war, is far beyond us (it may be beyond the White House, too). Whether tariffs can be an effective tool for incentivizing manufacturing is a little more discernible. And one thing is still for sure: Washington still (mostly) agrees that revitalizing manufacturing is a good idea.

The Means of Production

US manufacturing has been in clear structural decline for decades. The sector employs around 12.7 million workers in the US, according to the most recent figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s way down from the peak of around 19.5 million manufacturing workers in 1979, but also about 1 million more than the sector’s low point back in 2010.

As a share of GDP, the manufacturing sector has decreased from a nearly 25% peak in the 1950s to about 11% today. Globally, the sector has similarly seen a decline in share of GDP, contributing about 15% these days, though the US has seen a slightly more dramatic dropoff.

Still, the US has seen tremendous growth since the 1950s, when GDP routinely ran in the $425 billion range. So why the meltdown over the shifting tides?

Take Your Medicine

Like just about every other nationwide fear or anxiety, concern over a lack of domestic manufacturing was exacerbated by the Covid pandemic. Suddenly, off-shore supply chains seemed not just geopolitically risky but also tangibly expensive. The lead time to secure ultra-valuable semiconductors, for instance, ballooned from three to four months pre-pandemic to over a year in 2021 and 2022, according to S&P Global.

In pharmaceuticals, the vulnerabilities appeared even more stark: The US imports about 75% of its essential medicines, according to a recent industry analysis by supply chain logistics firm Exiger, while 60% of the key active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are sourced from India and China. Which brings us to our next reason for manufacturing’s bipartisan support.

Rising Tide: While the Covid crisis revealed vulnerabilities in supply chains and critical industries, bipartisan consensus to incentivize domestic manufacturing had been building in the past decade anyway. Why? The trade war elephant in the room: China and its incredible rise as a global manufacturing hub, export economy, and economic rival. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), between 2000 and 2023, China’s total global exports increased from $391 billion worth of goods (enough for fourth highest in the world) to $3.4 trillion, good for the top spot.

The US, meanwhile, has seen its total global exports increase in the same time from a top-ranked $807 billion to a runner-up $1.8 trillion (The US was also the top importer in the world in 2000, bringing in nearly $1.2 trillion worth of goods, which increased to about $3 trillion by 2023).

China’s manufacturing dominance is likely to increase even further:

- State-controlled banks have lent a stunning $1.9 trillion to fuel even more manufacturing in the past four years, according to a recent New York Times article.

- China already accounts for about 35% of the world’s gross manufacturing production, according to the most recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) figures, or more than the combined output of the US (12%), Japan (6%), Germany (4%), India (3%), and South Korea (3%).

For an illustration of what that investment means in practice, consider the famous Volkswagen manufacturing facility in Wolfsburg, Germany, which has long held the title of the most productive automobile plant in the world, capable of producing as many as 800,000 cars per year. Chinese electric-car manufacturer BYD is currently building two megaplants that could each produce double that amount in a single year.

“The tsunami is coming for everyone,” Katherine Tai, the United States trade representative during the Biden administration, told The New York Times.

Mythbusting: Still, some of these stats require more context. While globalized trade has allowed China to rise to the top of the manufacturing world, it’s just one reason US employment in the manufacturing sphere has plummeted — with many experts pointing to automation and productivity gains as chief causes for the decline. In fact, the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1992 appears not to have affected the rate of decline of manufacturing jobs in the US at all, according to BLS statistics.

Meanwhile, Mohammad Elahee, professor of international business at Quinnipiac University, told The Daily Upside that a significant portion of the growing US trade imbalance has been intra-firm deficits driven by advancements in logistics, digitalization, and the expansion of multinational subsidiaries in high-income markets — i.e., Ford or GM’s US units running a high trade deficit with their Mexico units.

It’s also worth noting that running a trade surplus or deficit one way or another is not necessarily indicative of the health of a country’s overall manufacturing sector. For instance, Germany routinely runs a trade surplus, yet has still experienced a decline in manufacturing jobs.

Playing Offense: Still, beyond shoring up supply chains and capacity for critical industries, there are plenty of sound economic reasons to make more things in America: Every dollar spent in manufacturing results in an additional $2.79 added to the economy, the highest multiplier effect of any sector, according to a 2022 Department of Defense report on maintaining key economic competitiveness.

And that’s not the only positive downstream effect created by a strong manufacturing industry that the Defense Department found:

- Every new manufacturing job also creates as many as seven to 12 new jobs in related industries.

- The industry also accounts for 55% of new patents in the US as well as 70% of research and development spending and 35% of productivity growth.

In short, a strong manufacturing base tends to be good for the economy. And here’s the good news: China’s massive investment in infrastructure the past four years has not gone unrivaled. In fact, dollars-to-dollars, it has effectively been matched by US policymakers. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act collectively pumped some $2.1 trillion into the domestic manufacturing sector, mostly into the production of highly complex and critical goods such as semiconductors and batteries for electric vehicles. It’s the type of high-value industry that the US still thrives in; the country remains a world leader in manufacturing technically complex products such as airplanes and weapons systems.

There are already early signs that the investments have been paying off. Between early 2021 and the summer of 2024, the US economy added about 750,000 new manufacturing jobs, according to a BlackRock report published in July. There were 482,000 manufacturing job openings in February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and a Deloitte report found that the sector may add another 3.8 million jobs by 2033. Meanwhile, construction spending in manufacturing — money spent to build or expand manufacturing facilities — hit a record of $238 billion in June 2024. Mentions of “reshoring” spiked 128% during earnings calls of S&P 500 companies in the first quarter of 2023, according to MDM Distribution Intelligence. (It should be noted that the DOGE budget-slashing initiative has already started cutting planned grants and subsidies that are a part of these programs.)

The above gains all occurred before President Trump took office again; since his inauguration earlier this year, foreign companies have pledged $1.9 trillion in investments in the US.

Playing Defense: The incentives represent the metaphorical carrot. How about the stick? If subsidies and investments play a role in kickstarting US manufacturing, can tariffs and protectionism play a role, too? Both sides of the political aisle would seem to think yes, to some extent. Tariffs increased by 85% from 2014 to 2022, according to BlackRock, spanning administrations. The Biden administration left in place tariffs as high as 25% on some Chinese imports first imposed during Trump 1.0.

In fact, some of these tariffs, too, have already proven to be effective. Tariffs on steel and aluminum, implemented in 2018 and maintained through the Biden White House, have already dampened imports as US production has increased. “Those are the industries that have started to adjust for quite some time,” Derek Lemke, senior vice president of product level intelligence at Exiger, told The Daily Upside. “A lot of buyers have changed their purchasing decisions.”

Trump 2.0 wants to test the theory to the extreme. Even after the quick rollback of some of the reciprocal tariffs imposed on Liberation Day, the newly imposed levies amount to by far the highest in the US in over 100 years. Theoretically, the tariffs should heavily disincentivize purchasing foreign imports and thus protect US manufacturing (some key advisors in the White House also believe that the tariffs could play a role in a coordinated effort to weaken the US dollar, thus making US-made goods more affordable in the global market, which would grow the manufacturing base; that theory, however, runs counter to most economists’ belief that tariffs tend to appreciate currency).

Already, industry is not so sure:

- The iShares U.S. Manufacturing ETF (MADE), which intends “to track the investment results of an index composed of US companies in manufacturing and manufacturing-related industries,” has fallen more than 8% since the Liberation Day announcements. The similarly-themed iShares Large Cap Value Active ETF (BLCV) is also down about 8% since the announcement.

- Meanwhile, GM, Ford, and Stellantis have tumbled 9%, 10%, and 20%, respectively, since Liberation Day. Tesla has fallen about 10%. BYD has slipped since Liberation Day, but is otherwise up some 35% year-to-date (the four US firms have all dropped so far this year).

So why the pessimism? For starters, the blanket tariffs don’t just apply to competitors’ goods, but to inputs in American manufacturing. In fact, about half of all US imports are inputs for US manufacturing companies, according to Associated Builders and Contractors Chief Economist Anirban Basu. That means margins for US manufacturers just shrank.

According to Elahee, the Quinnipiac professor, short-term tariffs can also be effective in protecting emerging industries, but in the long-term, “historically [tariffs] always do just the opposite of what politicians intend.”

Still, for defenders of tariffs, taxing manufacturing inputs is the point — so as to incentivize a radical reshoring of supply chains. But the rapidly changing terms of the trade war have driven up levels of uncertainty and restrained businesses from committing to the massive investments needed to reshore to the US. Plus, building out manufacturing infrastructure can take up to a decade in the first place.

“The amount of uncertainty that [the president] has introduced to the world trading system means that nobody is in a position to make long-term investments,” Teresa Fort, associate professor and international trade expert at Dartmouth College, recently told the Financial Times. “It is definitely going to make the US a less attractive place to invest in.”