Japan Looks to Leave its Lost Decades Behind

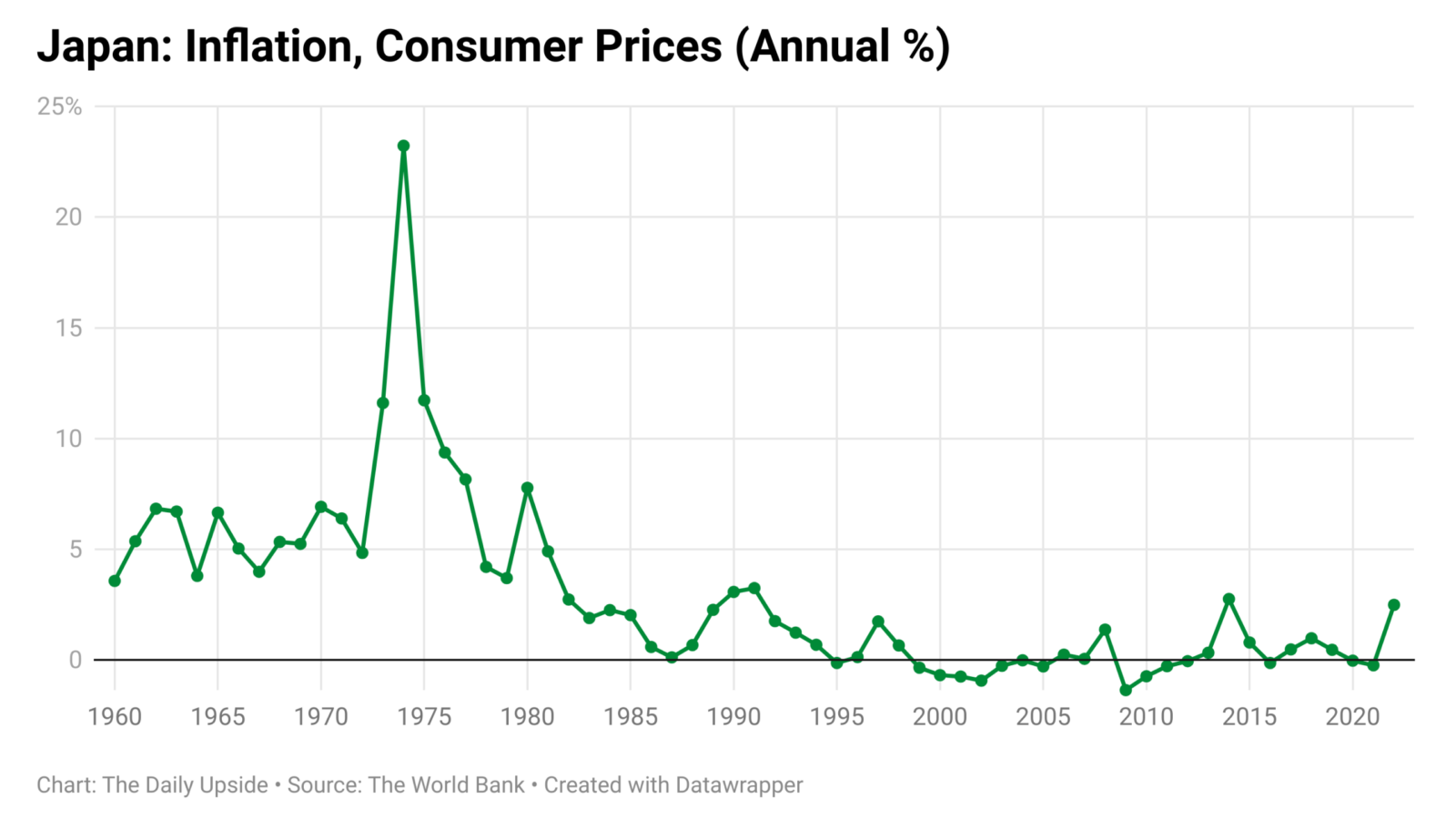

After years of chronic stagnation, prices are rising again, with inflation exceeding the Bank of Japan’s 2% target for two years running.

Sign up for smart news, insights, and analysis on the biggest financial stories of the day.

Sunday marks the final day of Japan’s Ōgon Shūkan, or Golden Week. The celebration commemorates four national holidays including one all about the joy of kids, which is somewhat ironic for an aging country trying to put decades of little to no economic growth behind it.

Little more than four months in, 2024 has been a heady if hectic time for Japan, the world’s third, er, fourth-largest economy, which has spent most of the past three decades in a Rip Van Winkle-like state but may be snapping out of it.

After years of chronic stagnation, prices are rising again, with inflation exceeding the Bank of Japan’s 2% target for two years running. The Nikkei Stock Market Index in turn has soared. In February, the index even hit a new high, breaching a record held since 1989. (It may have happened the same month Japan ceded the bronze-medal position for largest nominal GDP to Germany, but even the hypercompetitive Japanese didn’t seem to mind.)

By March, a confident BoJ ended the world’s most famous monetary policy experiment: eight years of negative interest rates and 17 years of no rate hikes. What the Japanese refer to as ushinawareta junen, or The Lost Decades, seemed to be at an end.

At the same time, the yen’s value against the US dollar has just sunk to its lowest level in 34 years, leading to billions in renewed BoJ intervention. The weak yen highlights the BoJ’s quandary as the US Federal Reserve defers interest-rate cuts, which would help ease the dollar’s climb against the yen. The gulf between the two currencies also illustrates that Japan still has to prove to investors that it’s completely busted out of its often deflationary trap.

Nihonomics 101

Understanding how Japan got here is simple: It had one of the world’s fastest-growing economies for much of the 20th century, and then it hit a slump that never abated.

The period after World War II was a full-on economic miracle. With massive investments in industrialization and legendary manufacturing acumen, Japan became the second-largest economy in the world, behind only the US — in some years during the 1960s, GDP grew by more than 10%.

Then came another kind of pop — the one that ends a bubble. But this was no typical bubble — it produced outlandish numbers like these:

- Land values in Tokyo increased 10% in 1986, 57% in 1987, and 22% in 1988, more than doubling in three years. At one point, real estate economists estimated that the few acres of land under the city’s Imperial Palace were worth more than all of the real estate in Canada.

- The real estate bubble coincided with a stock market boom, as firms were being valued with their massively appreciated real estate holdings in mind (uh-oh). The Nikkei Index rose every single year in the 1980s, culminating in speculator-fueled gains of 40% in 1988 and 29% in 1989.

- Capital gains in Japan from land and stocks in 1987 comprised more than 40% of the gross national product.

To rein in speculation, the Bank of Japan raised inter-bank lending rates in 1989, which burst the bubble. Japan’s stock market crashed — equities fell 60% between 1989 and 1992 — and real estate values tumbled along with them. After averaging around 4% in the 1980s, Japan’s annual GDP growth rate from 1992 to 2007 was barely above 1.1%, according to OECD data.

It didn’t help that lenders extended credit via “zombie loans” to insolvent firms, leaving them vulnerable again during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

As a result, people and companies in Japan became understandably cautious. In fact, they spent so little money that, by the late 1990s, prices were falling across the Japanese economy.

Japan’s central bank responded with classic Keynesian tricks of the trade to boost economic activity: Rates were lowered close to zero, money was printed, and the government went big on deficit spending. But the nation remained in a state of effective stagnation for most of two decades since — despite the BoJ introducing negative interest rates in 2016.

Inflate Expectations

Which brings us to 2024. In March, the BoJ raised its short-term interest rate to a whopping 0.0% to 0.1%, the first rate hike in 17 years. It also ended its yield curve control and scaled back asset purchases, two other key tools for quantitative easing.

So what changed? Simple: Japan has inflation again – remember, that’s good news for them. Prices have risen steadily, at or above the central bank’s 2% target, for two years. The latest data showed overall consumer prices climbed 2.7% in March from a year earlier.

A few factors are driving the new, inflated reality. Through the years of stagnation, Japanese companies often absorbed price increases in labor and raw materials to try and woo their frugal domestic consumers, which wasn’t great for profits. The pandemic, which brought rising import costs and supply chain disruptions, helped to normalize price hikes. Shrinkflation happened, too, with multiple websites tracking the phenomenon, in which companies ask consumers to pay the same for less, down to the last potato chip.

Workers, meanwhile, who saw virtually no growth in pay during the Lost Decades, have finally started to see wage increases, giving them more money to spend.

From 1991 to 2022, average pay in Japan rose just a total of 2.8%. Over the same period, average pay across countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) rose 32.5% (The low pay also coincided with low productivity: Japan ranked 30th in labor productivity among the OECD’s 38 members in 2022.)

However, last month Japan’s largest labor federation, Rengo, said that the average wage hikes gained during the annual shunto, or spring labor offensive, were 5.2%, the highest in 33 years. These gains have been encouraged by government policies set to take effect this year, chief among them a tax reform package that lets companies raise wages through tax breaks.

These two factors even feed off one another: The global inflation in the wake of the pandemic led to loud calls for wage increases from both the government and industrial associations. BoJ Governor Kauo Oeuda said in March that wages and stable inflation could form a “virtuous cycle” that would allow the government to continue to draw down stimulus measures.

So, while inflation may have become the bane of your existence and might be good fodder for US politicos to shout about, a little bit of it can actually be a good thing.

When it’s low, stable, and predictable, inflation is easy to capture in price-adjustment contracts that account for changes in labor and material costs. It also encourages consumers to spend sooner rather than later, knowing things will be pricier in the future. That’s Japan’s goal.

Not Finished: This doesn’t mean the legacy of the Lost Decades has been entirely solved — consumption is still fragile, and the economy narrowly missed a technical recession with 0.4% annualized growth in the most recent quarter — but it does mean the BoJ no longer thinks it needs an arsenal of policies to boost inflation. After more than a quarter century of interventions, that’s a big deal.

The Land of the Rising Index (and the Falling Yen)

For much of the Lost Decades, the Nikkei 225 index’s gains mirrored Japan’s meager inflation and growth numbers.

But the Nikkei has climbed 14.8% this year. It certainly didn’t hurt the optimistic trend to win a full-throated endorsement from none other than Warren Buffett, who disclosed last year that his Berkshire Hathaway increased stakes in five Japanese trading companies. “They were selling at what I thought was a ridiculous price, particularly the price compared to the interest rates prevailing at that time,” Buffett told CNBC. And during a visit last year, superfan Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s top asset manager, proclaimed Japan to be on the cusp of its next economic miracle.

Even after the recent rally, however, many Japanese stocks have remained at depressed levels — LSEG data reported by Reuters in February suggested over a third of the companies on the Nikkei 225 trade below their book value, compared to just three 3% on the US’ S&P 500.

Profits at listed Japanese companies are expected to hit a record high for the third year in a row for the fiscal year ended March 31, according to Nikkei Asia, with a 13% jump from a year earlier. Nikkei Asia noted that price hikes and the weak yen are contributing to these robust earnings.

Manufacturers like Toyota have benefited from a strong US economy coupled with the weak currency, while the semiconductor industry received a boost from nearly $25 billion in subsidies between 2021 and 2023, a higher proportionate investment than the US or Germany. Japan is also benefiting from so-called friend-shoring as Western nations and their allies rejigger supply chains to reduce their dependence on China.

But even when prices and animal spirits rise, challenges abound. Yowai en, or the weak yen, is probably the most immediate concern for Japan’s policymakers. While it’s great for exporters, it means more expensive imports, namely fuel and raw materials that will raise production costs and eat into profits.

Already, the BoJ may have hit a breaking point. After the yen fell to a 34-year low of 160 per dollar on April 29, The Wall Street Journal reported that Japanese authorities intervened by buying yen and selling dollars. No announcement was made, but official Bank of Japan data suggests the country may have spent 5.5 trillion yen ($35 billion) that day and another 3.66 trillion yen ($23.7 billion) Wednesday.

The yen finished the week at 152 per dollar, but the BoJ nevertheless remains at least partly at the mercy of the US Fed. Still dealing with high inflation stateside, Chairman Jerome Powell has backed away from language suggesting rate cuts are imminent, something that would likely weaken the dollar (higher US interest rates mean a stronger dollar because dollar assets like US bonds become more attractive). As of Friday, the US dollar index, which measures the greenback against a basket of currencies, had gained 3.3% this year.

But, after 30 years of deflation and stagnation, there could be worse punishments than waiting around for Jerome Powell.